The existing early care and education (ECE) system does a disservice to the educators — largely women and often women of color — who nurture and facilitate learning for millions of the nation’s youngest children every day. Despite their important, complex labor, early educators’ working conditions undermine their well-being and create devastating financial insecurity well into retirement age. These conditions also jeopardize their ability to work effectively with children.

As we find ourselves in the middle of a global pandemic, child care has been hailed as essential, yet policy responses to COVID-19 have mostly ignored educators themselves, leaving most to choose between their livelihood and their health. Unlike public schools, when child care programs close, there’s no guarantee that early educators will continue to be paid. Even as many providers try to keep their doors open to ensure their financial security, the combination of higher costs to meet safety protocols and lower revenue from fewer children enrolled is leading to job losses and program closures. Many of these closures and lost jobs are expected to become permanent. Over the course of the first eight months of the pandemic, 166,000 jobs in the child care industry were lost. As of October 2020, the industry was only 83 percent as large as it was in February, before the pandemic began. 1 CSCCE calculation of women employees in the child day care services industry between February 2020 and August 2020. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Data Viewer: Women employees, thousands, child day care services, seasonally adjusted. Retrieved from https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES6562440010.

Why is the ECE workforce expected to shoulder so much of the care and education crisis in this country, with so little concern for their own safety and well-being? It is no coincidence that this expectation falls on early educators, who are poorer, less organized as a workforce, and more likely to be women of color than teachers of older children. 2 Whitebook, M., Austin, L.J.E., & Williams, A. (2020). Is child care safe when school isn’t? Ask an early educator. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/data-snapshot/california-child-care-in-crisis-covid-19/.

Key Issue

Compared with early educators, teachers in the K-12 system can more readily expect their work environment to support their economic, physical, and emotional well-being. For example, K-12 teachers typically can rely on a salary schedule that accounts for experience and level of education, paid professional development activities, paid planning time each week, and access to benefits like paid personal/sick leave, health care, and retirement. Public school teacher unions and professional organizations help channel K-12 teachers’ collective voice and represent their interests. As a result, their negotiated contracts tend to be explicit about teaching supports. 1 Whitebook, M., & McLean, C. (2017). Educator Expectations, Qualifications, and Earnings: Shared Challenges and Divergent Systems in ECE and K-12. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/educator-expectations-qualifications-and-earnings/.

Most early educators lack a formal or organized mechanism for voicing concerns and influencing decisions about their working conditions and about how their ECE programs are financed and structured. Overall, unionization among early educators is much lower than among K-12 teachers. 2 As of 2018, the union membership rate was 4.8 percent of child care workers, compared with 14 percent for preschool/kindergarten teachers and 45 percent of elementary and middle school teachers, see Hirsch, B., & Macpherson, D. (2018). Union Membership and Coverage Database from the CPS. Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment by Occupation, 2018. Retrieved from http://unionstats.gsu.edu/. However, collective bargaining has been an effective strategy for improving supports for at least some home-based providers in recent years. In Massachusetts, a law establishing collective bargaining rights for home-based providers receiving child care subsidies has led to provisions for paid sick leave as well as paid family and medical leave. 3 Department of Early Education and Care (n.d.). Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For Massachusetts FFY 2019-2021. Massachusetts: Department of Early Education and Care. Retrieved from https://www.mass.gov/lists/child-care-and-development-fund-ccdf-state-plans; Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2020). Paid Family and Medical Leave for EEC-Subsidized Family Child Care Providers. Massachusetts: Department of Early Education and Care. Retrieved from https://www.mass.gov/service-details/paid-family-and-medical-leave-for-eec-subsidized-family-child-care-providers. Similarly, under contracts negotiated by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), home-based providers accrue paid sick leave in Rhode Island. 4 Department of Human Services (n.d.). Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For Rhode Island FFY 2019-2021. Rhode Island: Department of Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.ri.gov/Regulations/CCDF2019-2021StatePlan.pdf. In 2019, California joined at least 11 other states in granting collective bargaining rights to home-based providers, which may lead to additional supports. 5 Stavely, Z. (2020). California family child care providers vote to join union. Ed Source. Retrieved from https://edsource.org/2020/california-family-child-care-providers-vote-to-join-union/637229; 12 states have collective bargaining rights for family child care (California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington), from personal communication with Isaiah Wilson at SEIU via the National Women’s Law Center, September 1, 2020.

These efforts demonstrate the necessity of an organized voice and leadership structure composed of early educators themselves for effecting true and lasting change.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the historical and pervasive undervaluing of labor performed by women and especially women of color had created one of the most underpaid workforces in the United States. Economic insecurity is widespread among the ECE workforce, regardless of years of tenure in the field or higher education degrees. And as difficult as it is for anyone to be an early educator in America, it’s even worse for Black and Latina women, who face persistent wage gaps and belong to communities hardest hit by the pandemic. 3 Obinna, D. (2020). “Essential and undervalued: health disparities of African American women in the COVID-19 era.” Ethnicity & Health. DOI: 10.1080/13557858.2020.1843604.

Continuing to pay early educators poverty-level wages out of an expectation that women, especially women of color, will continue to do this work for (almost) free — either out of love for children or because they have few other options — perpetuates sexism, racism, and classism in the United States. Disrupting historical notions of early education and care as unskilled and of little value requires social recognition of early educators’ crucial contributions and a re-imagining of the entire early care and education system.

Early educators’ poor working conditions are not inevitable, but a product of policy choices that have consistently let down the women who are doing this essential work. It’s time for the system to change. Making early care and education an attractive field now and in the future means fundamentally reshaping early childhood jobs to provide fair compensation and reasonable working conditions, not least during a pandemic that continues to pose serious health and financial risks to early educators. Not only will this change make a meaningful difference to the financial lives of current and future early educators, but it will be a major step toward recognizing the value of historically feminine work and establishing a racially and gender-just society.

“The burden of school closures and parents continuing to work falls on child care providers. We need to be properly recognized through appropriate funding, PPE, and support systems. The government is largely ignoring the particularly unique burden that is put on child care during this pandemic.”

Child Care Center Director, California 4 Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Doocy, S., Kim, Y., & Montoya, E. (2020, July 22). California Child Care in Crisis: The Escalating Impacts of COVID-19 as California Reopens. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/data-snapshot/california-child-care-in-crisis-covid-19/.

Since 2016, the biennial Early Childhood Workforce Index has tracked the status of the early care and education workforce and related state policies in order to identify promising practices for improving early educator jobs and changes over time. This third edition includes new analyses as well as updated policy indicators and recommendations. Highlights include:

To view state assessments in previous editions of the Early Childhood Workforce Index , see:

Across almost all settings in the country, early educators are in economic distress, and this reality falls disproportionately on women of color and on those working with the youngest children (infants and toddlers). 5 Austin, L.J.E., Edwards, B., Chávez, R., & Whitebook, M. (2019). Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employment. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/racial-wage-gaps-in-early-education-employment/; Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from http://cscce.berkeley.edu/topic/early-childhood-workforce-index/2018/. Early care and education fails to generate sufficient wages that would allow early educators to meet their basic needs. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the child care industry, progress toward better compensation has been limited and uneven across states and among different classifications of early educators.

In this report, when we speak to policies, programs, and financing for the early childhood workforce, we align our boundaries of the workforce with those articulated by the International Labour Office (ILO) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The ISCED defines early educators as those who are “responsible for learning, education, and care activities of young children” and working in programs that are “usually school-based or otherwise institutionalized for a group of children (for example, center-, community-, or home-based), excluding purely private family-based arrangements that may be purposeful but are not organized in a program (for example, care and informal learning provided by parents, relatives, friends, or domestic workers).” 6 International Labour Office, Sectorial Activities Department (2014). Meeting of Experts on Policy Guidelines on the Promotion of Decent Work for Early Childhood Education Personnel. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_236528.pdf.

We focus primarily on those who work in teaching and administrative roles in early care and education settings serving children prior to kindergarten. We also compare the status of early educators to those teaching older children in order to highlight disparities in working conditions for educators across the birth-to-age-eight spectrum of early childhood development. 7 Early childhood as a developmental stage of learning for children includes the period from birth to age eight. However, existing education systems, policy structures, and professional organizations are typically bifurcated between those working with children age five and under/prior to school age and those working in the K-3 grades (age 5-8) school system. For more information, see Institute of Medicine (IOM) & National Research Council (NRC) (2015). Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/19401/transforming-the-workforce-for-children-birth-through-age-8-a.

A wide variety of terms are used to refer to the early care and education sector and its workforce depending on the age of children served (e.g., infants and toddlers, preschool-age children), the location of the service (centers, schools, or homes), auspice and funding streams, job roles, and data sources. We use “early childhood workforce” or “early educators” to encompass all those who work directly with young children for pay in early care and education settings in roles focused on teaching and caregiving. We use more specific labels, such as “Head Start teacher” or “home-based provider” when we are referring to a particular type of setting. In some cases, we are limited by the labels used in a particular data source. For example, in some instances, we refer to “childcare workers” and “preschool teachers” because we relied on data specific to subcategories of the workforce as defined and labeled by the Standard Occupational Classification of the U.S. Department of Labor.

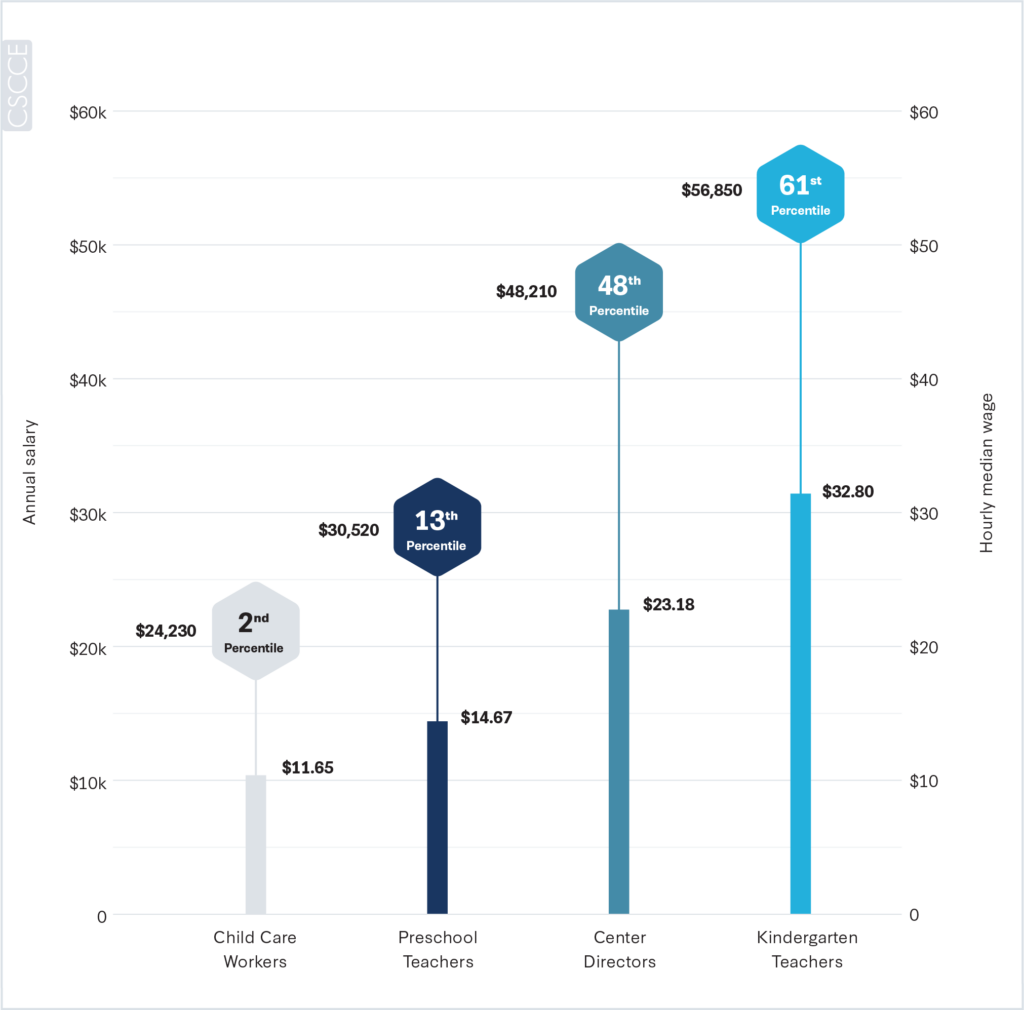

The most recent (2019) state-level wage data attest to the persistent low wages of early educators, as well as earnings disparities across early childhood settings and in comparison to other teaching jobs and occupations. Child care workers in particular continue to be one of the lowest-paid occupations nationwide. When all occupations are ranked by annual pay, child care workers remain nearly at the bottom percentile, unchanged since the inaugural 2016 Index (see Figure 1.1).

For a single adult with one child, median child care worker wages do not meet a living wage in any state, yet many early educators are themselves also parents, with children at home.

For a single adult with no children, median child care worker wages in only 10 states (Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming) are equivalent to or more than the living wage for that state. In the majority of states, wages fall short of the living wage for a single adult, from just under the living wage in Montana (short by $0.13), to as much as $3.39 less per hour in Hawaii (see Figure 1.2). The median gap between the child care wage and livable wage threshold across all states is -$0.96, meaning around one-half of the states are at least $1.00 per hour short of the threshold for a living wage for a single adult. For a single adult with one child, median child care worker wages do not meet a living wage in any state, yet many early educators are themselves also parents, with children at home.